A free and transparent electoral process, without external interference or manipulation.

This is the expectation of the European Union for the local elections in Kosovo on Sunday, October 12.

This week, Kosovo’s President, Vjosa Osmani, and acting Prime Minister, Albin Kurti, claimed that Serbia is interfering in the elections by offering jobs or financial aid to the Serb community.

The EU did not respond to Radio Free Europe’s request for comment on these allegations.

It also did not receive a response to the question of whether the EU is aware of any external influence on voters ahead of the local elections.

However, an EU spokesperson told Kosovo’s public broadcaster (RTK) that “all citizens should be able to exercise their right to vote freely, without external interference or manipulation.”

He recalled that the EU observation mission for the parliamentary elections in February had determined that there was external influence.

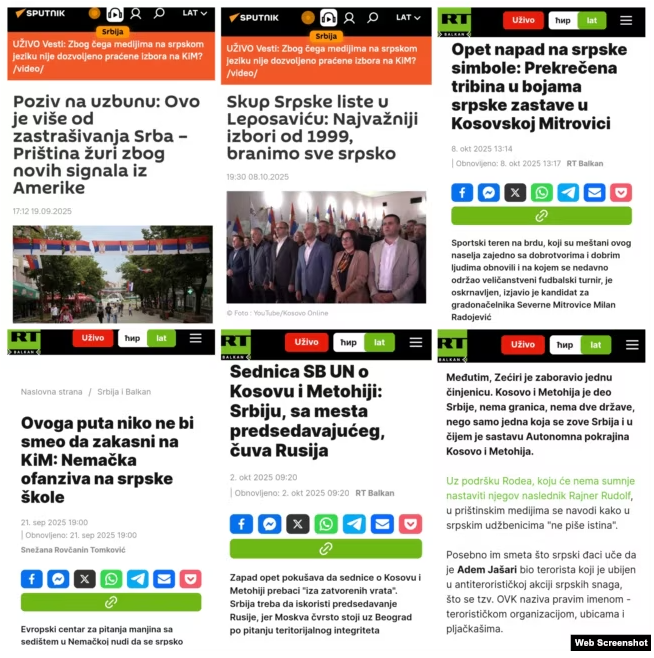

This observation mission revealed in its report that Russian state media, RT Balkan and Sputnik Serbia—which are supported by the Kremlin—published dozens of pieces of content about the elections in Kosovo during the campaign, containing “manipulative information” for the Serb community.

Jeta Loshaj, a researcher at the Kosovo Center for Security Studies, tells Radio Free Europe that these Russian media act as “agenda setters in sensitive political moments, such as elections, by portraying events through the lens of the victimization of the Serb community in Kosovo and the hostility of the West towards Serbia and Russia.”

“A clear example emerged during the campaign for the parliamentary elections in February 2025 [Note: date likely an error in original text], when RT Balkan and Sputnik published articles claiming there had been vote manipulation against Kosovo Serbs—claims that were then broadcast by pro-government Serbian media and Telegram channels active in northern Kosovo,” says Loshaj, who researches Russian influence in the Western Balkans countries.

In this context, she notes that “Russian influence in shaping public discourse and perceptions—especially among Kosovo Serbs—remains significant.”

What kind of narrative do Russian media spread during the campaign?

According to a Radio Free Europe analysis, during the pre-election campaign for the local elections in Kosovo, RT Balkan and Sputnik Serbia spread almost the same narrative as during the campaign for the parliamentary elections held on February 9: Lista Serbe (Serb List), the largest party of Kosovo Serbs that enjoys Belgrade’s support, is presented as the “defender of the interests” of the Serb community.

Kosovo authorities, on the other hand, are portrayed as those who exert only pressure or “terror” on the Serb community to force them to leave.

Other Serb political parties receive almost no coverage, or are described as “traitors” who cooperate with the Kosovo authorities.

For example, a news item on RT Balkan on October 8 stated that Serbian symbols in North Mitrovica were “targeted by vandals.” However, the news was based only on the words of Millan Radojeviq, the Serb List candidate, and there was no verification from the police or any other source.

The same medium published a news item on October 2, titled “UN Security Council Session on Kosovo and Metohija: Russia, from the chairing position, defends Serbia,” which stated that Serbia should benefit from Russia’s presidency because Moscow strongly supports Belgrade on the issue of territorial integrity, unlike Western countries.

And, in the article titled “This time no one should be late for Kosovo and Metohija: German offensive against Serbian schools,” published on September 21, there was talk of the proposed integration of Serbian health and education institutions into Kosovo’s system.

In that article, the former German ambassador to Kosovo, Jorn Rohde, was presented as the “custodian defender of the Albanians.”

In one section, the article’s author wrote that the “fact that Kosovo and Metohija is part of Serbia, there are no borders, there are not two states, but only one—called Serbia, which includes the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija” is being forgotten.

“They are particularly bothered by the fact that Serbian students learn that Adem Jashari was a terrorist, killed during an anti-terrorist operation by Serbian forces, and that the so-called Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) is described by its true name—as a terrorist, murderous, and plundering organization,” the text stated.

Sputnik Serbia sent similar messages. In an article on October 8, it broadcast the Serb List’s statement that the upcoming elections are the most important since 1999, because “everything Serbian will be protected.”

This medium regularly follows the pre-election rallies of the Serb List, where messages for the need for unity are conveyed, while other political entities are not mentioned at all.

Alternatives to the Serb List in the local elections in Serb-majority municipalities in Kosovo will be: Nenad Rashiq’s Freedom, Justice and Survival Party, Aleksandar Arsenijeviq’s Serbian Democracy, Millija Bishevac’s Serbian National Movement, Goran Marinkoviq’s Kosovo Alliance, as well as several civic initiatives.

In the article “Alarm Call: This is more than intimidation of Serbs – Pristina is rushing due to new signals from America,” Sputnik Serbia wrote on September 19 that citizens of North Mitrovica had informed the Serb List about “armed persons,” while interlocutors said the goal was to “at least frighten” the Serb population.

“The Serb List regularly warns that provocations aim to create an atmosphere of insecurity, so that Serbs are discouraged from staying in their homes. This paves the way for gradual emigration and the weakening of the Serb community, which is the main goal of those who want Kosovo cleansed of the Serb presence,” the text stated, among other things.

Otherwise, the “armed men” were members of the police or security forces of Kosovo’s acting Prime Minister, Albin Kurti, who visited North Mitrovica to meet with the candidates of his party, Vetëvendosje Movement, in the upcoming local elections.

What is the reach of these media?

Loshaj says that Russian state media, such as RT Balkan and Sputnik Serbia, do not prioritize providing information, but “repeating the Kremlin’s narrative.”

“Their direct reach is limited, but their indirect influence remains significant, as they push narratives into the wider sphere of Serbian-language information, which are then broadcast by regional tabloids, portals, and social networks,” Loshaj tells Radio Free Europe.

Reporters Without Borders, in last year’s report titled “From Russia to Serbia: How RT spreads Kremlin propaganda in the Balkans, despite EU sanctions?”, stated that RT Balkan’s content is quoted in media in Serbia, including the public service – Radio Television of Serbia.

“RT is quoted as a reliable source of news related to Russia, and as a result, RT Balkan functions as a state news agency, similar to Russia’s TASS,” the report stated.

Kosovo has imposed sanctions on RT and Sputnik, in line with the European Union’s policy and the sanctions imposed on Russia due to the invasion of Ukraine.

Therefore, the television channels of these media are not available on cable operators. However, their online platforms are occasionally available, due to—as the Regulatory Authority for Electronic and Postal Communications of Kosovo previously told Radio Free Europe—”the dynamic nature of the internet.”

Loshaj believes that Russian influence through the disinformation campaign will continue to grow, although, as she says, the direct impact on the audience is likely to remain limited, due to regulatory measures in Kosovo and the public’s focus on socio-economic issues.

“Disinformation affects interethnic relations”

Loshaj adds that disinformation narratives can influence interethnic relations or voter behavior in Kosovo, reinforcing existing feelings of dissatisfaction and distrust between communities.

She emphasizes that a study by the Kosovo Center for Security Studies, titled “How disinformation fuels ethno-political radicalism in Kosovo,” published in mid-September, highlighted that disinformation in Kosovo operates through a “mirror narrative,” informing two different communities in a completely opposite manner—adapted to their beliefs and perceptions.

“The goal is to reinforce division and distrust between groups. The Kosovo Serb audience is told that Kosovo institutions discriminate against them, while the Kosovo Albanian audience is told that Serbs in Kosovo are spoilers or linked to foreign powers,” Loshaj explains.

The center’s research also showed that narratives like those in the Russian media aim to undermine the credibility of Kosovo institutions and Western partners, such as the EU and NATO.

Such a thing, according to the research, can increase the risk of security incidents.

“This aligns with the broader goals of the Kremlin to portray the Western Balkans as an unstable periphery where the EU ‘is failing’,” Loshaj tells Radio Free Europe.

She adds that such narratives are also politically important during election campaigns because they aim to “delegitimize democratic processes and polarize interethnic relations.”

According to Loshaj, similar mechanisms were observed during the 2022 elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the 2020 elections in Montenegro, where pro-Russian media presented the vote as a “struggle for identity” rather than a choice of policies.

Ivana Stradner, a fellow at the Washington-based non-governmental Foundation for Defense of Democracies, previously told Radio Free Europe that Russia “knows the sensitive points in the region very well” and “gladly uses the role of religion and ethnic tensions in its operations.”

US Ambassador Whitaker Says Trump Has ‘Many’ Cards To Bring Peace To Ukraine

US Ambassador Whitaker Says Trump Has ‘Many’ Cards To Bring Peace To Ukraine  Serbia’s Narrative Against Kosovo and Turkey Over Turkish Drones

Serbia’s Narrative Against Kosovo and Turkey Over Turkish Drones  Russia blocks mobile data and text messages for European roaming customers

Russia blocks mobile data and text messages for European roaming customers  Terras: Serbia’s interference in Kosovo’s local elections unacceptable

Terras: Serbia’s interference in Kosovo’s local elections unacceptable  Tsikhanouskaya’s office in Vilnius still operating despite reduced security

Tsikhanouskaya’s office in Vilnius still operating despite reduced security  German media reports: “Kurschluz” has happened, Vučić must choose between plague and cholera

German media reports: “Kurschluz” has happened, Vučić must choose between plague and cholera